Authors: Aakash Pattabi and Eric Gilliam

“The world clings to its old mental picture of the stock market because it’s comforting; because it’s so hard to draw a picture of what has replaced it; and because the few people able to draw it for you have no interest in doing so.”

― Michael Lewis, Flash Boys

On a good day the crews were able to lay two to three miles of it in the ground. Progress was smooth until the crews arrived in Western Pennsylvania. There the pace slowed to a few hundred feet a day. The experienced crews laying the fiber optic cables through the walls of hard limestone did not know what the line was for or where it would lead.

The estimated cost of the line was $300 million. Its purpose: speed.

This cable and its pervasive effects on Wall Street were the subject of the best selling book Flash Boys by Michael Lewis. This new fiber optic cable from the mercantile exchange in Chicago to the stock exchanges in New York could send signals from Chicago to New York and back in close to the theoretically optimal time of 13 milliseconds (a millisecond is one thousandth of a second). Construction of this cable began less than two years after the onset of the Great Recession. The next best line at the time, controlled by Verizon, could do this same job in 14.65 milliseconds, too slow.

Arbitrage

Whenever one trader knows something others don’t, there is money to be made. If someone knows more about the financial statements of Coca Cola’s stock than another trader in the market, then they stand a pretty good chance of making some money on that trade. That’s a trade worth betting on, but it’s not a sure thing. Unforeseen things can still go wrong for Coca-Cola.

This risk does not exist in arbitrage. In an arbitrage trade the investor seeks to exploit differences in price that occur in identical or almost identical stocks on different exchanges. For example, the S&P 500 stock trades on the NYSE and NASDAQ exchanges in New York City. S&P futures contracts, which allow traders to bet on the future value of S&P 500 stock, are traded at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. What these futures contracts are worth is determined by whether traders believe that the S&P 500’s value will go up or down. So, the value of the futures contracts and the stock should rise and fall together.

An arbitrage trader seeks to find disparities in prices between exchanges. If a disparity exists, then the traders can sell the more expensive security and use that money to buy the other. It’s free money. The traders are selling one security and using the money to buy even more of an almost identical security. If you can find the disparities, profit is guaranteed.

The incentives of speed

The firm responsible for the construction of the slightly more efficient fiber optic cable route, Spread Networks, was far from crazy for undertaking this $300 million project.

Michael Lewis reports, the first 200 slots offering access to the cable were sold for a total of $2.8 billion.

Buying access to this additional millisecond and a half does not create anything new. It gives the high frequency traders the opportunity to ensure that a larger proportion of the money earned from milliseconds long price inefficiencies goes to them instead of to some other trader. Billions of dollars were and still are being spent to reshuffle the money allocated to the winners of milliseconds long market inefficiencies.

Not only are billions being spent on ensuring only those who could pay to access the fastest cables can engage in arbitrage, it is also attracting some of the brightest minds in the country.

In Flash Boys, Michael Lewis writes:

“The new players in the financial markets, the kingpins of the future who had the capacity to reshape those markets, were a different breed: the Chinese guy who had spent the previous ten years in American universities; the French particle physicist from Fermilab; the Russian aerospace engineer; the Indian PhD in electrical engineering. There were thousands of these people,’ said [John] Schwall [founder of the IEX Stock Exchange]. ‘Basically all of them with advanced degrees. I remember thinking to myself how unfortunate it was that so many engineers were joining these firms to exploit investors rather than solving public problems.’”

One can blame the banks for spending money in such ways, those building the fiber optic cable lines for creating a monster, or the bright STEM PHD’s for engaging in work that merely reshuffles money won from arbitrage. It is not the job of these companies and bright STEM PHD’s, however, to ignore the incentives to which they are responding.

Many, such as economists Eric Budish, Peter Cramton, and John Shim, believe there is an effective way to reduce the lucrative incentives of high frequency trading through government regulation. The proposed solution is something called frequent batch auctions.

What is a frequent batch auction?

The way the current market works, being ten thousandths of a second faster than another trader means you get the stock and they do not. A unit of time this small is only meaningful to those engaging in high frequency trading. Normal traders cannot even click their keyboard in anything close to ten thousandths of a second.

Instead of allowing something as trivial as a thousandth of a second to matter in the markets, frequent batch auctions treat every bid for a given stock in a given time period as coming in at the same time. For example, if someone wanted to batch by hundredths of a second, every bid that came in between 2:00.01 and 2:00.02 p.m. would be treated as if they came in at the exact same time. The stocks would then be allocated to those who bid during the same hundredth of a second by some mechanism other than time of trade.

Using this method, markets can remain intact for traditional traders, and spending billions on milliseconds could be disincentivized.

Simulating frequent batches

We decided to run a simulation on real trading data to see how frequent batch auctions might affect the markets. We used trading data sourced from LOBSTER, a system that has, since 2013, provided reconstructed order book data for academic use.

The data is only tracked at the frequency of a tenth of a second, but since arbitrage opportunities exist over all time horizons, this simulation will still provide useful insights for regulating high frequency trading.

We matched buyers and sellers within each batch as follows:

- All buy orders above the equilibrium price and all sell orders below this price are immediately executed.

- Some buy and sell orders at exactly the equilibrium price may not be executed, so orders at the equilibrium price are executed in random sequence until there are no more buy or sell orders.

The order books for Microsoft, Apple, Google, and Intel’s NASDAQ tickers are available free on the platform. These samples track the trades of each asset over one trading day in 2012. Even with only one day’s worth of order messages, we have access to almost 600,000 orders for each asset. We demonstrate our results on Microsoft data, but they are consistent across all of the above assets.

IEX Group, a three-year-old stock exchange, has received attention for implementing a 350 microsecond delay on all transactions occurring on their market, which they claim protects client orders from “being scalped at stale prices by certain high-speedtraders who have purchased faster access to information from other exchanges, and know the prices to be stale,”. IEX claims that such a delay protects regular trading clients from being beaten by high-frequency traders. These high-frequency traders would otherwise react to potential orders and remove liquidity on exchanges before regular clients can respond. The exchange’s critics suggest that while such a delay would benefit ordinary investors, it could create market inefficiency.

This simulation serves as a useful thought experiment in considering whether something like a batch auction or time delay would, in reality, create inefficiency.

How did frequent batch auctions change the market?

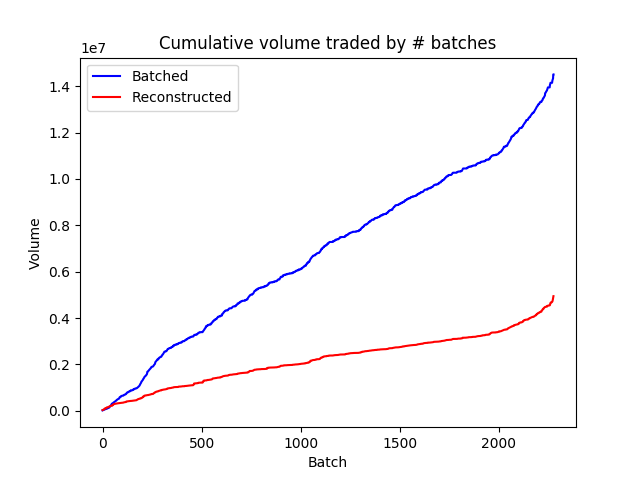

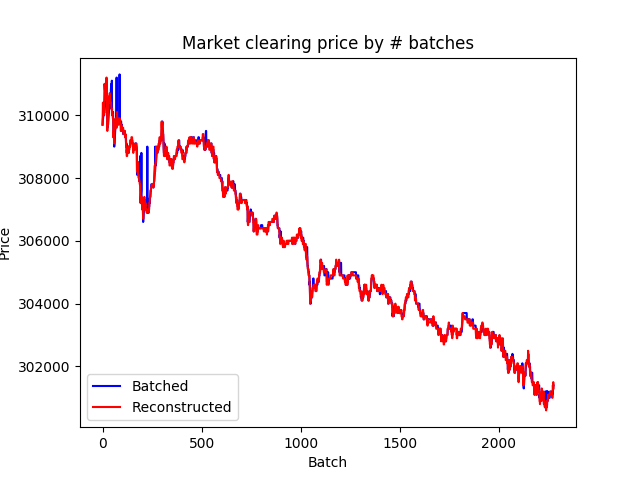

Using batch auctions on the stock data, we found that market clearing prices were unchanged. The number of matches made, also, was three times larger in the batched data than in the reconstructed, actual trading matches.

Not only did batch auctions leave prices almost unchanged, they made the market more efficient when it came to the number of matches made in the market. Economists would refer to this as maximizing welfare. Increasing the number of matches made for a given price theoretically maximizes welfare because you are finding a way to make more transactions happen for given supply and demand curves.

The simulated, batched data was made using the same buy and sell orders as in real life. Without changing prices, the batching mechanism was able to ensure that three times as many transactions were made.

This simulation, while just a thought experiment, ought to assuage the concerns of traders worried about regulatory policy undercutting market efficiency. Frequent batch auctions represent an effective regulation which can be used to de-escalate this high-frequency arms-race.

A better way forward

High frequency traders are willing to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars just to have their server closer to the New York Stock Exchange than a rival trader’s server in that same room, Lewis reported. These same traders were willing to pay to replace all of their existing trading hardware when new hardware was engineered that could make the same trades three milliseconds faster, 50 times as fast as the blink of an eye.

We have experienced how ugly things can get when every millisecond counts. It might be time for the government to step in and mandate that one hundredth of a second is fast enough, at least on Wall Street.